Using the 1863 Paddington to Farringdon route for an example, how was ventilation provided in the old cut-and-cover method of tunnel construction? Where were ventilation shafts installed and what was the average size? General rule of 1 every so many meters or so? And I'm assuming air-pressure between hot and cold as well as the movement of the steam engines through the tunnels created the necessary currents to draw hot air out?

-

Our booking engine at tickets.railforums.co.uk (powered by TrainSplit) helps support the running of the forum with every ticket purchase! Find out more and ask any questions/give us feedback in this thread!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Underground Steam Engine Ventilation in the Victorian Era

- Thread starter Chitin

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Sponsor Post - registered members do not see these adverts; click here to register, or click here to log in

R

RailUK Forums

Spartacus

Established Member

- Joined

- 25 Aug 2009

- Messages

- 2,914

In the main, it wasn't, at least on that route. Locos were fitted with condensing equipment which diverted much of the exhaust steam back to the water tanks, though not the smoke. It was lessened by using 'smokeless' coal, and earlier coke, but as this was meant to make conditions fine there was little to no attempt to provide additional ventilation. Even though most cities were a pretty grimy place to be back then conditions must have been pretty bad as there was a Board of Trade report into it in 1897 which recommended additional ventilation (stations had already lost their roofs and an opening created between Euston Square and Kings Cross) but the line was electrified before this was done.

Last edited:

The worst bit was between Edgware Road and Kings Cross, where it ran directly beneath the main road. Elsewhere on the Circle there were a significant number of short open spots, some still visible, others have been built over since electrification.

The Mersey Railway between Birkenhead Park and Liverpool central, a deep level line with underground stations, must have been worse.

Specific brands of coal/coke dealt with some of it in London, and condensing with the steam, which was not so much a noxious nuisance but could be a considerable quantity of exhaust. Because the steam was condensed in the loco side tanks the water in there would rise in temperature and lessen the effect, so at intervals the tanks were completely discharged and refilled, at Edgware Road and Aldgate.

My guess is that the two cross-Glasgow lines, through Queen Street and particularly Central, were even worse, as they did not employ condensing locos or special coal, and unlike the other two used steam right up to the 1960s.

The Mersey Railway between Birkenhead Park and Liverpool central, a deep level line with underground stations, must have been worse.

Specific brands of coal/coke dealt with some of it in London, and condensing with the steam, which was not so much a noxious nuisance but could be a considerable quantity of exhaust. Because the steam was condensed in the loco side tanks the water in there would rise in temperature and lessen the effect, so at intervals the tanks were completely discharged and refilled, at Edgware Road and Aldgate.

My guess is that the two cross-Glasgow lines, through Queen Street and particularly Central, were even worse, as they did not employ condensing locos or special coal, and unlike the other two used steam right up to the 1960s.

krus_aragon

Established Member

Here's a story that was first published in the English Illustrated Magazine in August 1893, and reprinted in the May/June 1944 issue of the Railway Magazine (from whence I copy it):

(Pictures are photographed on my phone and uploaded directly, forgive the lack of editing)

When the Circle was Steam Operated

By the courtesy of Mr. Powell, Manager of the District Railway, I was provided with an "engine-pass"for the "Inner Circle"; and on a bright June morning I made my way to St. James's Park Station. There I met Chief-Inspector Exall, who was detailed to accompany and look after me generally. The train selected was a District "down" one. "Down," by the way, signifies up to the Mansion House; the explanation of this apparent paradox being that the norther part of the "Circle" was opened first. In those days the line was only some 3 1/2 miles long, and yet cost over a million pounds to construct.

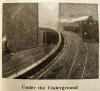

In a short time our train rushed into the station, and a moment later we had boarded the engine. I was accommodated with a position near the left-hand tank, whence I could get an uninterrupted view ahead; but it has its drawbacks as the water in that tank was hot. No time is wasted at stations on the Underground, and a minute later the train was off - off into a black wall ahead with the shrieking of ten thousand demons rising above the thunder of the wheels. The sensation altogether was much like the inhalation of gas preparatory to having a tooth drawn. I would have given a good deal to have waited just a minute or so longer. Visions of accidents, collisions, and crumbling tunnels floated through my mind; a fierce wind took away my breath, and innumerable blacks [smuts] filled my eyes. I crouched low and held on like grim death to a little rail near me. Driver, stoker, inspector, and engine - all had vanished. Before and behind, and on either side was blackness, heavy, dense, and impenetrable.

Westminster Bridge, Charing Cross and the Temple were passed before I could do or think of anything beyond holding on to that rolling, rushing engine; then finding that I was still alive and sound, I began to look about me. Inspector Exall put his head to my ear and shouted something at the top of his voice, but I could only catch the word "Blackfriars." I looked ahead. Far off in the distance was a small square-shaped hole, seemingly high up in the air, and from it came four silver threads palpitating like gossamers in the morning breeze. Larger and larger grew the hole, the threads become rails, and the hole a station; Blackfriars, with rays of golden sunlight piercing through the gloom.

Off again, a fierce light now trailing behind us from the open furnace door, lighting up the fireman as he shovelled more coal on the furnace, throwing great shadows into the air, and revealing overhead a low creamy roof with black lines upon it that seemed to chase and follow us. Ever and anon the guard's face could be dimly seen at his window, more like a ghost than a man; while in the glass of the look-out holes were reflected the forms of engine-men, like spirits of the tunnel mocking us from the black pit into which we were plunging. Then again we would seem to stop, and to fall down, down, with always the wild shrieking surge and ceaseless clatter of the iron wheels.

Soon ahead of us gleamed pillars of crimson stars, the signal lights of the Mansion House. Between this station and Mark Lane there is nothing particularly noticeable, saving the approach to the latter; where ghostly-looking figures paced a hidden platform across which fell great golden beams that looked like impassable barriers. Yet, ere one could take a second glance, the beams were riven asunder and a black engine blotted them out with clouds of writhing steam.

Next to Mark Lane, and almost close to it, is the old Tower Station,* now disused. We sped past its deserted platforms and limp signal posts, and a few minutes later steamed into the central station, Aldgate. The fireman at once leapt off the engine and made the necessary arrangements for filling our water tanks. So quickly was this done that probably none of the passengers noticed any difference in the length of the stoppage, and in a very short while we were off again into the tunnels, two minutes sufficing to bring us round a sharp curve into Bishopsgate.

*[Tower of London Station was opened on September 25, 1882, as the terminus of a short Metropolitan Railway branch from Aldgate. It was closed on the evening of October 12, 1884, a week after the completion of the Inner Circle.]

*[Bishopsgate Station on the Metropolitan Railway was renamed Liverpool Street on November 1, 1909]

Aldersgate, the next station, was opened in 1865, and for many years it was comparatively deserted by passengers. The opening of the markets hard by has altered all this, and it is now one of the principal stations on the line. All about this section we encountered other lines which sometime dived under us, at other times merely diverged in various directions. Outside Aldersgate the line is ventilated by a series of arches, which give a fine effect of light and shade, making the tunnel look like an old time dungeon.

From Farringdon Street to Kings Cross is the longest stretch without a station, and the driver here gave us an exhibition of full speed, and No. 18 came into King's Cross at the rate of some 40 m.p.h. The average speed of trains between one station and another is from 20 to 25 m.p.h.

The road now began to be more uphill, and at the same time the air grew more foul. From King's Cross to Edgware Road the ventilation is defective, and the atmosphere on a par with the " 'tween decks, forrud" of a modern ironclad in bad weather, and that is saying a good deal. By the time we reached Gower Street* I was coughing and spluttering like a boy with his first cigar. "It is a little unpleasant when you ain't used to it," said the driver with the composure born of long usage, "but you ought to come on a hot summer's day to get the real thing!" Fog on the underground appears to cause less inconvenience than do sultry days of July; then the atmosphere is killing. With the exception of this one section (between Kings Cross and Edgware Road) I found the air far purer than I had expected, and the bad air so much complained of by the "sewer-rates" - as those who habitually use this circle are called in "the City" - is due in a great measure to their almost universal habit of keeping all the windows and ventilators closed.

The finest bit of scenery on the underground is the Baker Street Junction, where a second tunnel leading to the St. John's Wood line branches out of the main one. It is no longer used for through trains, however, owing to a fearful accident that occurred here some time ago,* and Baker Street is now the terminus of that line. On the left through the main tunnel lies the station, a medley in crimson and gold; on the right the daylight creeps in, and the picture is a harmony in blue and silver. It is a novel and unexpected sight to see the ordinary black coat of respectability look crimson, as it does when seen after the intense blackness of the tunnel. But like all the other scenes, this was brief and momentary; then a dream of the past. There is a similar and much-used junction before Praed Street, but it is provided with a big signal box where the tunnels meet.**

*[The St. John's Wood Railway was opened on April 13, 1868, but the through service to Moorgate Street ceased on March 8, 1869. It was resumed on July 1, 1909, over a single-line connection. The new double-line junction at Bake Street was brought into use on November 4, 1912.]

**[There was, however, a collision at Praed Street Junction in February 18, 1891]

(Pictures are photographed on my phone and uploaded directly, forgive the lack of editing)

When the Circle was Steam Operated

By the courtesy of Mr. Powell, Manager of the District Railway, I was provided with an "engine-pass"for the "Inner Circle"; and on a bright June morning I made my way to St. James's Park Station. There I met Chief-Inspector Exall, who was detailed to accompany and look after me generally. The train selected was a District "down" one. "Down," by the way, signifies up to the Mansion House; the explanation of this apparent paradox being that the norther part of the "Circle" was opened first. In those days the line was only some 3 1/2 miles long, and yet cost over a million pounds to construct.

In a short time our train rushed into the station, and a moment later we had boarded the engine. I was accommodated with a position near the left-hand tank, whence I could get an uninterrupted view ahead; but it has its drawbacks as the water in that tank was hot. No time is wasted at stations on the Underground, and a minute later the train was off - off into a black wall ahead with the shrieking of ten thousand demons rising above the thunder of the wheels. The sensation altogether was much like the inhalation of gas preparatory to having a tooth drawn. I would have given a good deal to have waited just a minute or so longer. Visions of accidents, collisions, and crumbling tunnels floated through my mind; a fierce wind took away my breath, and innumerable blacks [smuts] filled my eyes. I crouched low and held on like grim death to a little rail near me. Driver, stoker, inspector, and engine - all had vanished. Before and behind, and on either side was blackness, heavy, dense, and impenetrable.

Westminster Bridge, Charing Cross and the Temple were passed before I could do or think of anything beyond holding on to that rolling, rushing engine; then finding that I was still alive and sound, I began to look about me. Inspector Exall put his head to my ear and shouted something at the top of his voice, but I could only catch the word "Blackfriars." I looked ahead. Far off in the distance was a small square-shaped hole, seemingly high up in the air, and from it came four silver threads palpitating like gossamers in the morning breeze. Larger and larger grew the hole, the threads become rails, and the hole a station; Blackfriars, with rays of golden sunlight piercing through the gloom.

Off again, a fierce light now trailing behind us from the open furnace door, lighting up the fireman as he shovelled more coal on the furnace, throwing great shadows into the air, and revealing overhead a low creamy roof with black lines upon it that seemed to chase and follow us. Ever and anon the guard's face could be dimly seen at his window, more like a ghost than a man; while in the glass of the look-out holes were reflected the forms of engine-men, like spirits of the tunnel mocking us from the black pit into which we were plunging. Then again we would seem to stop, and to fall down, down, with always the wild shrieking surge and ceaseless clatter of the iron wheels.

Soon ahead of us gleamed pillars of crimson stars, the signal lights of the Mansion House. Between this station and Mark Lane there is nothing particularly noticeable, saving the approach to the latter; where ghostly-looking figures paced a hidden platform across which fell great golden beams that looked like impassable barriers. Yet, ere one could take a second glance, the beams were riven asunder and a black engine blotted them out with clouds of writhing steam.

Next to Mark Lane, and almost close to it, is the old Tower Station,* now disused. We sped past its deserted platforms and limp signal posts, and a few minutes later steamed into the central station, Aldgate. The fireman at once leapt off the engine and made the necessary arrangements for filling our water tanks. So quickly was this done that probably none of the passengers noticed any difference in the length of the stoppage, and in a very short while we were off again into the tunnels, two minutes sufficing to bring us round a sharp curve into Bishopsgate.

*[Tower of London Station was opened on September 25, 1882, as the terminus of a short Metropolitan Railway branch from Aldgate. It was closed on the evening of October 12, 1884, a week after the completion of the Inner Circle.]

*[Bishopsgate Station on the Metropolitan Railway was renamed Liverpool Street on November 1, 1909]

Aldersgate, the next station, was opened in 1865, and for many years it was comparatively deserted by passengers. The opening of the markets hard by has altered all this, and it is now one of the principal stations on the line. All about this section we encountered other lines which sometime dived under us, at other times merely diverged in various directions. Outside Aldersgate the line is ventilated by a series of arches, which give a fine effect of light and shade, making the tunnel look like an old time dungeon.

From Farringdon Street to Kings Cross is the longest stretch without a station, and the driver here gave us an exhibition of full speed, and No. 18 came into King's Cross at the rate of some 40 m.p.h. The average speed of trains between one station and another is from 20 to 25 m.p.h.

The road now began to be more uphill, and at the same time the air grew more foul. From King's Cross to Edgware Road the ventilation is defective, and the atmosphere on a par with the " 'tween decks, forrud" of a modern ironclad in bad weather, and that is saying a good deal. By the time we reached Gower Street* I was coughing and spluttering like a boy with his first cigar. "It is a little unpleasant when you ain't used to it," said the driver with the composure born of long usage, "but you ought to come on a hot summer's day to get the real thing!" Fog on the underground appears to cause less inconvenience than do sultry days of July; then the atmosphere is killing. With the exception of this one section (between Kings Cross and Edgware Road) I found the air far purer than I had expected, and the bad air so much complained of by the "sewer-rates" - as those who habitually use this circle are called in "the City" - is due in a great measure to their almost universal habit of keeping all the windows and ventilators closed.

The finest bit of scenery on the underground is the Baker Street Junction, where a second tunnel leading to the St. John's Wood line branches out of the main one. It is no longer used for through trains, however, owing to a fearful accident that occurred here some time ago,* and Baker Street is now the terminus of that line. On the left through the main tunnel lies the station, a medley in crimson and gold; on the right the daylight creeps in, and the picture is a harmony in blue and silver. It is a novel and unexpected sight to see the ordinary black coat of respectability look crimson, as it does when seen after the intense blackness of the tunnel. But like all the other scenes, this was brief and momentary; then a dream of the past. There is a similar and much-used junction before Praed Street, but it is provided with a big signal box where the tunnels meet.**

*[The St. John's Wood Railway was opened on April 13, 1868, but the through service to Moorgate Street ceased on March 8, 1869. It was resumed on July 1, 1909, over a single-line connection. The new double-line junction at Bake Street was brought into use on November 4, 1912.]

**[There was, however, a collision at Praed Street Junction in February 18, 1891]

krus_aragon

Established Member

The ventilating holes in the tunnel roof all about this part give a beautiful effect of light striking into darkness; especially one before Edgware Road is reached, where the silver column of light fell on a green signal lamp, set low in the permanent way. Just before Praed Street we got into daylight again - the line passing through a sort of valley formed by high houses on each side.

Hitherto, though we had passed many, I had scarcely noticed the trains that we met; but about here I changed over to the right side of the engine in order to get a better view of a coming train. I had not long to wait. Far away in the distance was an ever-increasing speck of light - the headlight of an approaching train. A moment later it had come and gone - a silent flash of light, so silent that it might have been a phantom; our own engine made too much noise for any other sound to be audible. Curiously enough, an approaching train is totally unlike what one would imagine it ought to look like. A strong light bursts from the furnace if it chances to be open, and illuminates the tunnel overhead, the carriage windows and brass work make line of light that run off and die in the distance, but the engine itself is lost in the blackness through which it is rushing.

At High Street, Kensington, engines are changed so we jumped off - at least my guide did - my attempt to follow his example being calculated to cause an impression that I had taken the platform to be a seat - but all this is by the way. Engine No. 18 went off into a shed to rest awhile, and No. 7, a precisely similar one, backed on to the train in her place. This resting of engines is rendered a frequent necessity from the strain caused by the numerous stoppages; incessant running in one direction has also been found to be bad for them as it wears away the wheels on one side sooner than the other. To remedy this, the engines half the time run "backwards forwards," as they say in the West of England.

Off again; and this time down-hill. We dashed rapidly through the grass embankments outside Gloucester Road, past some men posting bills on the advertisement hoardings that border the line below South Kensington, now deep in a tunnel, now traversing a cutting open to the sky; until we shot once more into St. James's Park, 70 min. after leaving it. We had covered some 13 miles in our trip round London; seemingly no great distance for the time occupied; till one recollects that it entailed no less than 27 stoppages, with a watering and change of engines into the bargain. It is these stoppages that make he journey as long as it is; if a train went round at its usual rate it would be back at the starting point in less than 40 min., while if it went full speed some 20 min. would suffice.

However the 70-min. trip is quite rapid enough for all practical purposes, and is only rendered possible by excellence of the brake arrangements, and the perfection to which the block-system of signaling has now been brought. The length of the stoppages could not well be reduced; indeed, they are already too short if we are to believe the tale now current of a wandering Jew sort of passenger - a lady of advanced years who can only alight from a train backwards. Every time she begins to get out a porter rushes up crying, "Hurry up, ma'am; train's going!" - and pushes her in again!

"This finishes our journey," said the inspector, as, taught by experience, I cautiously crawled off the engine, - "unless you'd like to go round again." I declined.

- Written and illustrated by our Artist-Commissioner. [Fred T Jane]

Hitherto, though we had passed many, I had scarcely noticed the trains that we met; but about here I changed over to the right side of the engine in order to get a better view of a coming train. I had not long to wait. Far away in the distance was an ever-increasing speck of light - the headlight of an approaching train. A moment later it had come and gone - a silent flash of light, so silent that it might have been a phantom; our own engine made too much noise for any other sound to be audible. Curiously enough, an approaching train is totally unlike what one would imagine it ought to look like. A strong light bursts from the furnace if it chances to be open, and illuminates the tunnel overhead, the carriage windows and brass work make line of light that run off and die in the distance, but the engine itself is lost in the blackness through which it is rushing.

At High Street, Kensington, engines are changed so we jumped off - at least my guide did - my attempt to follow his example being calculated to cause an impression that I had taken the platform to be a seat - but all this is by the way. Engine No. 18 went off into a shed to rest awhile, and No. 7, a precisely similar one, backed on to the train in her place. This resting of engines is rendered a frequent necessity from the strain caused by the numerous stoppages; incessant running in one direction has also been found to be bad for them as it wears away the wheels on one side sooner than the other. To remedy this, the engines half the time run "backwards forwards," as they say in the West of England.

Off again; and this time down-hill. We dashed rapidly through the grass embankments outside Gloucester Road, past some men posting bills on the advertisement hoardings that border the line below South Kensington, now deep in a tunnel, now traversing a cutting open to the sky; until we shot once more into St. James's Park, 70 min. after leaving it. We had covered some 13 miles in our trip round London; seemingly no great distance for the time occupied; till one recollects that it entailed no less than 27 stoppages, with a watering and change of engines into the bargain. It is these stoppages that make he journey as long as it is; if a train went round at its usual rate it would be back at the starting point in less than 40 min., while if it went full speed some 20 min. would suffice.

However the 70-min. trip is quite rapid enough for all practical purposes, and is only rendered possible by excellence of the brake arrangements, and the perfection to which the block-system of signaling has now been brought. The length of the stoppages could not well be reduced; indeed, they are already too short if we are to believe the tale now current of a wandering Jew sort of passenger - a lady of advanced years who can only alight from a train backwards. Every time she begins to get out a porter rushes up crying, "Hurry up, ma'am; train's going!" - and pushes her in again!

"This finishes our journey," said the inspector, as, taught by experience, I cautiously crawled off the engine, - "unless you'd like to go round again." I declined.

- Written and illustrated by our Artist-Commissioner. [Fred T Jane]

Last edited:

The Mersey Railway between Birkenhead Park and Liverpool central, a deep level line with underground stations, must have been worse.

It wasn't popular, precisely as the atmosphere was so unpleasant. It's little wonder it was electrified in 1903.

Merthyr Imp

Member

In a bid to solve the problem of the smoke a species of fireless locomotive was tried out by the Metropolitan Railway but proved a failure:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fowler's_Ghost

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fowler's_Ghost

Harbornite

Established Member

- Joined

- 7 May 2016

- Messages

- 3,634

The ventilating holes in the tunnel roof all about this part give a beautiful effect of light striking into darkness; especially one before Edgware Road is reached, where the silver column of light fell on a green signal lamp, set low in the permanent way. Just before Praed Street we got into daylight again - the line passing through a sort of valley formed by high houses on each side.

Good stuff, thanks for sharing.

This may seem strange, as the normal remedy for wear on one side is to alternate the mileage in each direction. However, the sharing arrangement between the Met and the District on the Circle had one doing all the running in one direction, the other the opposite. Running the locos backwards half the time seems a poor solution, compared to altering the sharing arrangement.This resting of engines is rendered a frequent necessity from the strain caused by the numerous stoppages; incessant running in one direction has also been found to be bad for them as it wears away the wheels on one side sooner than the other. To remedy this, the engines half the time run "backwards forwards," as they say in the West of England.

Was this the headquarters of the District at such an early time? I am aware the District's owners later built a new HQ there about 1905, and of course London Transport then built their 55 Broadway headquarters there in the 1930s, but it was a small wayside point, not one of the principal operating points around the Circle.I made my way to St. James's Park Station. There I met Chief-Inspector Exall

He's obviously been around for a long time then ... was he innocent?"Bill Stickers in danger at South Kensington"

Last edited:

krus_aragon

Established Member

From the description of the hot water tank I believe they were condensing the exhaust steam. I forget where I read this (online, this week!), but engines operating in this manner would have to be "rested" regularly and have their tanks flushed out, as referred to in the above piece. If you've got to take your engines to the shed every few hours, then it may be just as easy to turn them at the same time, as opposed to the bureaucracy of sharing engines between companies.This may seem strange, as the normal remedy for wear on one side is to alternate the mileage in each direction. However, the sharing arrangement between the Met and the District on the Circle had one doing all the running in one direction, the other the opposite. Running the locos backwards half the time seems a poor solution, compared to altering the sharing arrangement.

krus_aragon

Established Member

Thanks for filling in the gaps in my memory.Condensing the steam in the tanks eventually made the water too hot for the injectors to work hence the reason for the complete exchange of water.

randyrippley

Established Member

- Joined

- 21 Feb 2016

- Messages

- 5,132

Surely the uneven wheel wear was due to the fact the locos were essentially always running a circle, with one side always on the inner rail of the circle. Thats bound to give uneven wear, nothing to do with direction of travel. Turning the loco would resolve that.

You'd also have the same problem with the coach wheelsets as well

You'd also have the same problem with the coach wheelsets as well

Yes, precisely. The loco was turned, but the direction of travel couldn't be reversed as each direction was operated by a different company. So for this reason they had to operate, err, "tender first" (how do you say that for a tank engine?).Surely the uneven wheel wear was due to the fact the locos were essentially always running a circle, with one side always on the inner rail of the circle. Thats bound to give uneven wear, nothing to do with direction of travel. Turning the loco would resolve that.

You'd also have the same problem with the coach wheelsets as well

krus_aragon

Established Member

The article suggested "backwards forwards" . As an alternative, how about "tank first", " boiler behind", or maybe "funnel following" ?

Condensing engines were commonly fitted with feed water pumps instead of injectors, precisely to handle the issue of warm water. They are universal on steamships, for example, where the supply of (fresh) water has to be recirculated.

The coaches could be periodically reversed on one of the several triangles around the system without it being noticeable. Loco servicing points at High Street Ken and Aldgate were both next to triangles.

I do believe I read an account in the past that the hot water was discharged from the loco, and fresh introduced, while attached to the train, at one of the various points where it stood for a couple of minutes and was serviced, in an operation that took no longer than changing locos would. Presumably there were drainage pans at such points. There must have been a big steam cloud rising from such operations as well.

A common expression for tank engines running in reverse is "bunker first".

The coaches could be periodically reversed on one of the several triangles around the system without it being noticeable. Loco servicing points at High Street Ken and Aldgate were both next to triangles.

I do believe I read an account in the past that the hot water was discharged from the loco, and fresh introduced, while attached to the train, at one of the various points where it stood for a couple of minutes and was serviced, in an operation that took no longer than changing locos would. Presumably there were drainage pans at such points. There must have been a big steam cloud rising from such operations as well.

A common expression for tank engines running in reverse is "bunker first".

Last edited:

- Status

- Not open for further replies.